During a recent interview, a journalist asked me, “What is it that you like so much about midcentury modern design?” I responded that I'm attracted to the optimism of the postwar years, where the architects of the day felt like they could make the world a better place for everyone by combining good design with new wartime materials.

Those architects and builders of that era questioned the status quo, developing new and inexpensive ways of building homes, full of the latest labor-saving technology, often with only a single pane of glass separating the indoors from the outdoors. Even with new wartime technologies like plywood and steel framing, it took another 50 years for building technology to catch up with the designs of the architects. I'm pleased to report that we can now make flat roofs that don't leak, and walls of glass that are energy-efficient on these midcentury homes, an area of our practice that we're seeing a lot of interest in.

In these trying days, I feel our role as architects and designers remains the same: question everything that is thought to be obvious, and face our uncertain future with bravery, optimism, and creativity. This pandemic, like the ones before it, will pass, and my hope is when we emerge from it, we will use our skills and technology to create a better world for all people.

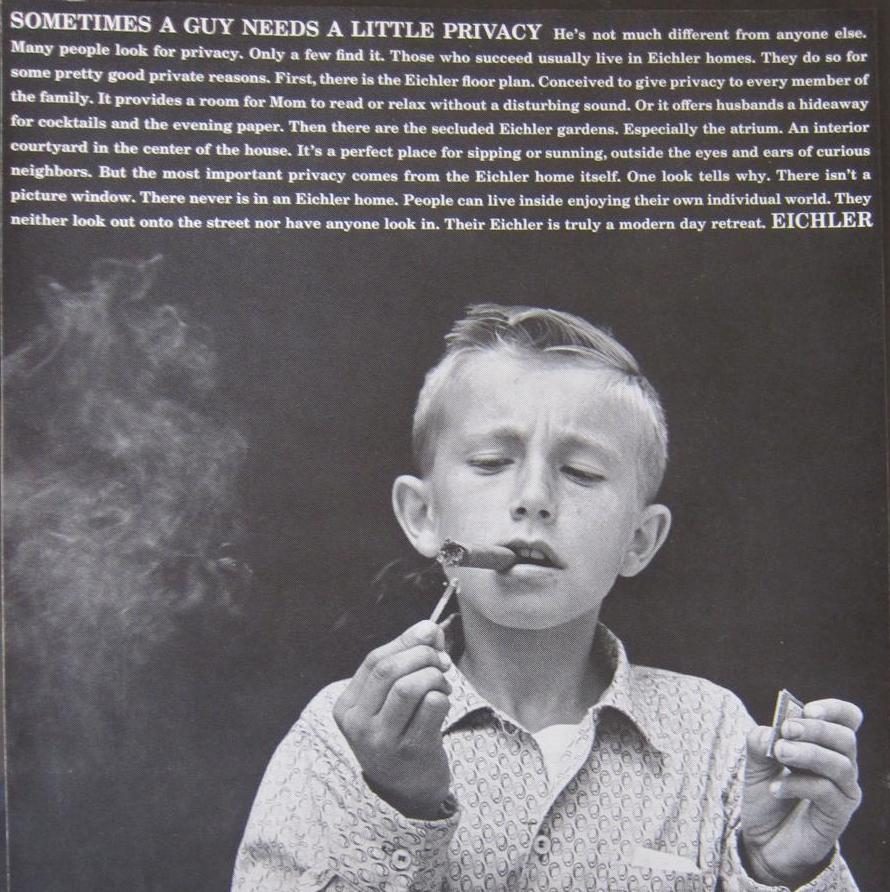

The optimism of the postwar years, in part, paved the way for social change. In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that racial restrictions written into property deeds were unconstitutional. Locally, in 1954, developer Joseph Eichler sold his first home to African-American buyers in Palo Alto. The next year, he received complaints again, this time from a group of neighbors in San Rafael after a home was sold to an African American family. Eichler responded angrily to their complaints, going “door-to-door personally to confront them and even offered to buy back their homes.” No one took the developer up on his offer, and he soon developed a reputation that he would sell to anyone based solely on their qualifications.